Ruthless Pursuit of Power: The Mystique of the C6 Corvette LS7 Engine - Page 9 of 26

Ruthless Pursuit of Power: Lucky Seven Edition: The Mystique of the 7-Liter, 7000-RPM, LS7 - Page 9 of 26

|

|

by Hib Halverson

© May 2013— Updated: November 2014

No use without permission, All Rights Reserved

Dry-Sump Oiling

The performance requirements Dave Hill's Corvette Team gave the folks at Powertrain were demanding: 500-hp, 7000 RPM and engine reliability under levels of acceleration, braking and cornering forces unattained by previous stock Corvettes. Computer modeling quickly demonstrated that, to meet those requirements, the Z06's wet sump oiling days were over. Even the best of GM's wet sumps, the fabled "bat-wing" oil pan of the C5 days, could not be relied upon for consistent oil flow at the LS7's lofty RPM range and at the Z06's gut-wrenching handling limits, so LS7 became the first production GM engine to use a dry sump oiling system.

"Our biggest surprise was Powertrain's choice of a dry sump." Katech's Fritz Kayl told us. "In the early parts of the program, we were able to show them what performance advantages you can get out of dry sump system, but we never thought they would consider it.

"We bid on doing the dry sump for that engine but we did not get it, so we weren't really involved in the production side too much. The actual production dry sump system running the scavenge pump off the crank, behind the pressure pump, I thought, was pretty unique and it works pretty well. Certainly not an all-out race set-up, but darn good for a production car."

Actually, "dry" sump is a misnomer because it's not truly dry, at least in the sense of some of the complicated dry-sump systems on C5-Rs, C6.Rs or a NASCAR Sprint Cup car. The LS7 system is more of a "semi-dry" sump in that there's oil inside the crankcase and the oil pan. What's different is the "sump" part--that is, the engine's entire oil supply--is not stored in the lower part of the oil pan beneath the crankcase, but rather in a remote-mounted tank. The oil pan contains a limited amount of oil, because, when the engine is running, it's constantly drained or "scavenged" by a "scavenge pump".

"GM had never developed one before," John Rydzewski began his discussion of the dry sump. "We benchmarked systems on racing engines and from other manufacturers which have (production) dry sumps like Porsche and Ferrari. We saw how complicated they are. You can do a very complex, multi-scavenge with each (crankcase) bay scavenged individually by a pump having five stages, like on a race engine. That's the extreme and not what we wanted for this car. We wanted something to give us the performance we needed. We wanted it more affordable. We wanted to make it as compact as possible."

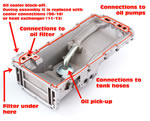

The LS7 development team settled on a two-stage design. Gen 3/4 engines already had crankshaft-driven, gerotor oil pumps, so it made sense to add a second gerotor scavenge pump. Both are inside a two-cavity housing located at the normal oil pump position on the front of the block.

Oil is sucked out of the bottom of the pan, into the scavenge pump, through a passage in the bottom of the pan, then through hoses and into the dry sump tank located in the right rear corner of the engine compartment. Oil enters the bottom of the tank and flows through a tube to the top of the tank. Flow then reverses through a system of baffles and perforations, down the inside perimeter of the tank. That spiraling, downward flow separates the air and crankcase gases out of the oil.

The lower part of the tank is the engine's oil reservoir. The air and gases rise to the top, are ingested by the Positive Crankcase Ventilation (PCV) system and consumed by the engine.At the bottom of this tank is conditioned oil--"conditioned" meaning the vast majority of air and gases are gone and it's a little bit cooler because it's been in the tank for a while. On top of that, as the engine is subjected to accelerating, braking and cornering forces, the pick-up tube is always submerged. It doesn't suck air and that's the key to the reliable, consistent oil supply an LS7 needs. The system first had an 8-quart tank, but when the ZR-1 came out three years later, because of LS9's greater oil flow demand driven by its piston oilers, a supplemental, two-quart tank was added. The 10-qt. dual-tank configuration ended-up being used for all three of the Gen IV dry-sump engines, LS3, -7 and -9.

Like most road racing engines, the LS7's dry-sump system includes an engine oil cooler. For the first four years, the cooler was the oil-to-air type located in the "cooling stack" ahead of the engine along with the coolant radiator and the air conditioning condenser. In 2011, to reduce cost, complexity and weight along with increasing parts commonality with the LS9, the '06-'10 cooler was replaced on Z06es with an oil-to-coolant heat exchanger, bolted to the oil pan on the driver side of the engine, along with the LS9's higher-capacity, all-aluminum coolant radiator.

|

|